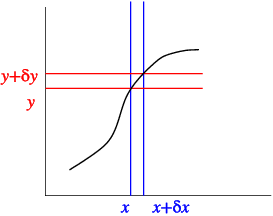

If y = f(x) and x increases from x to x + δx then the change in y is give by δy = f(x + δ) − f(x), see Fig. 4.1. The differential is defined as

|

\class{boxed}{ {dy\over

dx} ={\mathop{ lim}}_{δx→0} {δy\over

δx} = {\mathop{lim}}_{δx→0}{f(x + δx) − f(x)\over

δx} . }

|

The derivative can also be interpreted as the slope of a curve, see Fig. 4.2. If the slope at a given point has an angle θ, we find that \mathop{tan}\nolimits θ is {dy\over dx}. In other words, the line y − {y}_{0} =\mathop{ tan}\nolimits θ\kern 1.66702pt (x − {x}_{0}) is tangent to the curve at ({x}_{0},{y}_{0}).

The differential of a sum is the sum of differentials,

|

\class{boxed}{ {d(u + v)\over

dx} = {du\over

dx} + {dv\over

dx}. }

|

L&T, F.9.26-27

There exists a simple rule to calculate the differential of a product,

|

\class{boxed}{ {d(uv)\over

dx} = u{dv\over

dx} + v{du\over

dx}. }

|

E.g., if y = {x}^{2}\mathop{ sin}\nolimits x,

|

{dy\over

dx} = {x}^{2}\mathop{ cos}\nolimits (x) + 2x\mathop{sin}\nolimits (x)\quad .

|

L&T, F.9.28-30

In the same way we can find a relation for the differential of a quotient,

|

\class{boxed}{ {d({u\over

v})\over

dx} = {v{du\over

dx} − u{dv\over

dx}\over

{v}^{2}} . }

|

E.g., if y = {\mathop{sin}\nolimits x\over x} ,

|

{dy\over

dx} = {x\mathop{cos}\nolimits (x) −\mathop{ sin}\nolimits (x)\over

{x}^{2}} = {\mathop{cos}\nolimits (x)\over

x} −{\mathop{sin}\nolimits (x)\over

{x}^{2}} \quad .

|

L&T, F.9.33-36,7.5-18

Often we take a function of a function. In such a case, where y = f(g(x)) we put z = g(x), and find

|

\class{boxed}{ {dy\over

dx} = {dy\over

dz} {dz\over

dx}. }

|

This rule is sometimes expressed in words as “the derivative of the function, times the derivative of its argument”, and you may know it as

|

\class{boxed}{ {dg(f(x))\over

dx} = f'(g(x))g'(x). }

|

Example 4.1:

Find {dy\over dx} for y =\mathop{ cos}\nolimits (\mathop{ln}\nolimits x).

Solution:

Put z =\mathop{ ln}\nolimits x so y =\mathop{ cos}\nolimits z,

|

{dy\over

dx} = {dy\over

dz},\quad {dz\over

dx} = −\mathop{sin}\nolimits z {1\over

x} = −{\mathop{sin}\nolimits (\mathop{ln}\nolimits x)\over

x} \quad .

|

Example 4.2:

Find {dy\over dx} for y ={\mathop{ sin}\nolimits }^{3}(2x − 1).

Solution:

Put z =\mathop{ sin}\nolimits (2x − 1) so y = {z}^{3},

|

{dy\over

dx} = {dy\over

dz} {dz\over

dx} = 3{z}^{2}2\mathop{cos}\nolimits (2x − 1) = 6{\mathop{sin}\nolimits }^{2}(2x − 1)\mathop{cos}\nolimits (2x − 1)\quad .

|

Example 4.3:

Given that x(t) = 5{t}^{2}\text{ m}, find the velocity v(t) and the acceleration a(t).

Solution:

Using the definitions of velocity as rate of change of position, we find that v =\dot{ x} = {dx\over dt} = 10t\text{ m/s}, and with acceleration as rate of change of velocity, we have a =\dot{ v} =\ddot{ x} = {dv\over dt} = 10\text{ m/s${}^{2}$}.

Example 4.4:

For simple harmonic motion (SHM) x =\mathop{ cos}\nolimits (ωt). Find the velocity and acceleration.

Solution:

Use the change rule for differentiation, v =\dot{ x} = −ω\mathop{sin}\nolimits (ωt), a =\dot{ v} = −{ω}^{2}\mathop{ cos}\nolimits (ωt)

L&T, 9.8-13

When we wish to calculate the differential of an inverse function, i.e, a function g such that g(f(x)) = x, we can use our knowledge of the derivative of f to find that of g.

Example 4.5:

Find the derivative of y ={\mathop{ sin}\nolimits }^{−1}x.

Solution:

We use y =\mathop{ sin}\nolimits (x) and calculate {dx\over dy} first,

|

{dx\over

dy} = {\mathop{sin}\nolimits y\over

dy} =\mathop{ cos}\nolimits y.

|

Now \mathop{cos}\nolimits y = ±\sqrt{1 −{\mathop{ sin} \nolimits }^{2 } y}, but the slope of the inverse sine is always positive. Thus

|

{dy\over

dx} ={ \left ({dx\over

dy}\right )}^{−1} = {1\over

\sqrt{1 − {x}^{2}}}.

|

L&T, 9.24-31

At a maximum or minimum the slope is 0 so that {dy\over dx} = 0. To find which case it is, we look at {{d}^{2}y\over d{x}^{2}} , which can easily be done from a plot of the slope.

Example 4.6:

Find all maxima and minima of y = x(3 − x) and determine their character.

Solution:

We find that {dy\over dx} = x(−1) + (3 − x)1 = 3 − 2x. For a maximum or minimum the slope must be 0. This happens for 3 − 2x = 0, i.e., x = {3\over 2}. For that value of x, {{d}^{2}y\over d{x}^{2}} = −2. So the point x = 3∕2, y = 9∕4 is a (and the only) maximum.

L&T, F.9.21-22

Higher derivatives are obtained by differentiation 2 or more times, {{d}^{2}y\over d{x}^{2}} = {d(dy∕dx)\over dx} , {{d}^{3}y\over d{x}^{3}} = {d({d}^{2}y∕d{x}^{2})\over dx} .

Example 4.7:

y =\mathop{ ln}\nolimits x, {dy\over dx} = 1∕x, {{d}^{2}y\over d{x}^{2}} = −{1\over { x}^{2}} , {{d}^{3}y\over d{x}^{3}} = {2\over { x}^{3}} , etc.

Example 4.8:

The equation for simple harmonic motion (SHM) is {{d}^{2}x\over d{t}^{2}} = −{ω}^{2}x. Prove that x = (A\mathop{cos}\nolimits ωt) + B\mathop{sin}\nolimits ωt satisfies this equation.

Solution:

We must differentiate twice, start with first derivative, {dx\over dt} = (−ω)A\mathop{sin}\nolimits ωt + ωB\mathop{cos}\nolimits ωt, and find that

QED.

N.B.: SHM not studied here, but in next semester. The constants A, B can only be obtained with extra input.