Let me start this section by an example. A group of people is sitting around a circular table of radius a. A single light bulb is suspended above the table. What is the optimal height for the bulb, so that people have most light on their plates?

The amount of light on each plate is related to the area of the plate perpendicular to the light rays, but the intensity of light falls like 1∕{r}^{2}. Let A be the area of the plate, ϕ the angle the light rays make with the plate and table, and P the power emitted by the bulb, and r the distance from bulb to the centre of the plate. Then

|

\class{boxed}{ L = {PA\mathop{sin}\nolimits ϕ\over

4π{r}^{2}} . }

|

This is not yet in a suitable form, but we can express ϕ and r in terms of x, the height above the table,

|

\mathop{sin}\nolimits ϕ = x∕r,\qquad r = \sqrt{{x}^{2 } + {a}^{2}}.

|

This gives the dependence of L on x as

|

\class{boxed}{ {PA\over

4π} {x\over {

({x}^{2} + {a}^{2})}^{3∕2}}. }

|

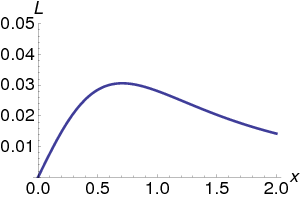

So how do we now choose x. The first thing is to sketch L(x). Let us use P = 100\text{ W}, A = 1{0}^{−2}\text{ m${}^{2}$}, and a = 1\text{m}. The first thing to do is to draw a curve (using whatever tool you prefer), see Fig. 4.9.

We see that there is a maximum, which we can find by differentiation,

This is zero when x = ±{1\over 2}\sqrt{2}a, and thus x = 0.707\text{ m}. Since f'(x) > 0 below this point and positive above, this is a maximum.

The greatest value over a given interval is called a global maximum, the smallest one a global minimum. A local maximum means that all points near the current one are smaller; a local minimum means that all points are larger.

A local minimum or maximum is usually determined by a zero derivative (unless the function isn’t differentiable); a local minimum or maximum can be a global one, but doesn’t have to be.

Example 4.19:

Find the global minimum and maximum of f(x) = {x}^{3} − 4x over 2 ≤ x ≤ 3.

Solution:

First look a stationary points, f'(x) = 0 leads to 3{x}^{2} − 4 = 0 or x = ±2∕\sqrt{3} ≈±1.155. These points lie within the interval! Now make a table

Thus the global minimum is − 3.079 (x = 2∕\sqrt{3}) and the maximum 15 (x = 3), as we can also see from a sketch, see Fig. 4.10.

With all the information we have about functions and derivatives, we can build up a much better picture of graphs and curves; we can give a few rules that will help us to do much better!

Example 4.20:

Sketch the curve y = {(x − 1)}^{2}(x − 2).

Solution:

This curve is not symmetric, and is defined for all x; no forbidden regions.

Intercept with x axis: x = 1 and x = 2. With y axis: y = −2.

For large x the function grows as {x}^{3}.

Derivative (x − 1)(3x − 5) is zero for x = 1 (f(x) = 0) and x = 5∕3 (f(x) = −4∕27).

Concavity: f'' = 6x − 8: negative at x = 1 (minimum), positive at 5∕3 (maximum).

| x | f(x) | f'(x) | remarks |

| -2 | -36 | 33 | |

| -1 | -12 | 16 | |

| 0 | -2 | 5 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | zero and local maximum |

| 5/3 | -4/27 | 0 | local minimum |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | intersects x axis |

| 3 | 4 | 8 |

The result is shown if Fig. 4.11.

Example 4.21:

Sketch the curve y = x∕(1 + {x}^{2}).

Solution:

This curve is antisymmetric (if x →−x, y →−y), and is defined for all x; no forbidden regions.

Intercept with x axis at x = 0 only; also intercept with y axis.

For large x y = {(x∕{x}^{2})\over 1+1∕{x}^{2}} ≈ 1∕x − 1∕{x}^{3}.

For small x (using geometric series) y = x − {x}^{3} + \mathop{\mathop{…}}.

Derivative (using quotient rule)

This is zero for x = ±1. From the second derivative {2\kern 1.66702pt x\kern 1.66702pt \left (−3+{x}^{2}\right )\over { \left (1+{x}^{2}\right )}^{3}} we find that x = 1 is a maximum, x = −1 a minimum. Together with y(x = 2) = 2∕5, y(x = 3) = 3∕10, we can now sketch the curve, see Fig. 4.12.

Example 4.22:

Sketch the curve y = {1+{e}^{x}\over 1−{e}^{x}}.

Solution:

If we take x →−x, then

The function is undefined when {e}^{x} = 1, i.e., x = 0.

The function is zero when 1 + {e}^{x} = 0 (i.e., never)!

For small x

{e}^{x} = 1 + x,

so y = −1∕x − 1 + \mathop{\mathop{…}}.

For large positive x

we can ignore the ones, and y →−1;

for large negative x

{e}^{x}

is negligible, and y → 1.

Derivative (using quotient rule)

|

{dy\over

dx} = {−{e}^{x}(1 + {e}^{x}) − {e}^{x}(1 − {e}^{x})\over

{(1 − {e}^{x})}^{2}} = {−2{e}^{x}\over {

(1 − {e}^{x})}^{2}}

|

from which we conclude that it is negative everywhere, no zeroes.

We can now sketch the curve, see Fig. 4.13.