Notice that in the Fourier series of the square wave (4.23) all coefficients {a}_{n} vanish, the series only contains sines. This is a very general phenomenon for so-called even and odd functions.

These have somewhat different properties than the even and odd numbers:

Question: Which of the following functions is even or odd?

a) \mathop{sin}\nolimits (2x), b)

\mathop{sin}\nolimits (x)\mathop{cos}\nolimits (x), c)

\mathop{tan}\nolimits (x), d)

{x}^{2}, e)

{x}^{3}, f)

|x|

Answer: even: d, f; odd: a, b, c, e.

Now if we look at a Fourier series, the Fourier cosine series

|

f(x) = {{a}_{0}\over

2} +{ \mathop{∑

}}_{n=1}^{∞}{a}_{

n}\mathop{ cos}\nolimits {nπ\over

L} x

| (4.28) |

describes an even function (why?), and the Fourier sine series

|

f(x) ={ \mathop{∑

}}_{n=1}^{∞}{b}_{

n}\mathop{ sin}\nolimits {nπ\over

L} x

| (4.29) |

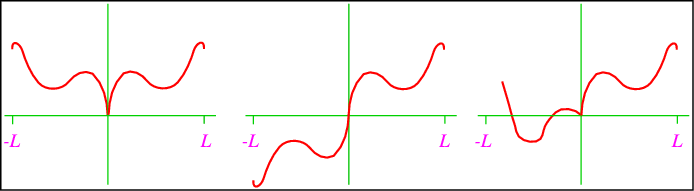

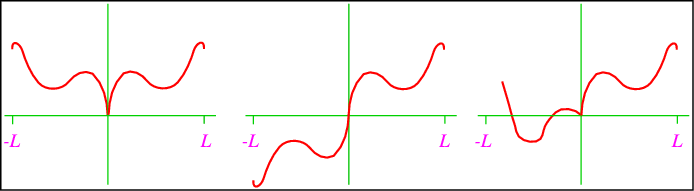

an odd function. These series are interesting by themselves, but play an especially important rôle for functions defined on half the Fourier interval, i.e., on [0,L] instead of [−L,L]. There are three possible ways to define a Fourier series in this way, see Fig. 4.2

Of course these all lead to different Fourier series, that represent the same function on [0,L]. The usefulness of even and odd Fourier series is related to the imposition of boundary conditions. A Fourier cosine series has df∕dx = 0 at x = 0, and the Fourier sine series has f(x = 0) = 0. Let me check the first of these statements:

As an example look at the function f(x) = 1 − x, 0 ≤ x ≤ 1, with an even continuation on the interval [−1,1]. We find

So, changing variables by defining n = 2m + 1 so that in a sum over all m n runs over all odd numbers,

|

f(x) = {1\over

2} + {4\over {

π}^{2}}{ \mathop{∑

}}_{m=0}^{∞} {1\over {

(2m + 1)}^{2}}\mathop{ cos}\nolimits (2m + 1)πx.

| (4.32) |